|

|

|---|---|

| Plate T-14 | Map |

|

|

|---|---|

| Plate T-14 | Map |

The second great segment of the depositional/deformational trough that lay along the convergent Paleozoic eastern and southern margins of the North American craton is the Ouachita orogenic system (Viele, 1973). The segment begins at a structural recess now buried under the eastern side of the Mississippi Embayment, swings northwestward, and then turns westward through the 360-km long Ouachita mountain belt of Arkansas and eastern Oklahoma, the western portion of which is seen in this Plate. It then turns southwestward (the change in trend is visible near the center of the Plate) through central Texas and extends west to the Marathon uplift. The Sierra Madre Oriental of the northeastern Mexican Cordillera truncates the trend in northern Mexico.

Both segments have considerable thicknesses of Lower Paleozoic carbonate sediments (in the scene, about 2000 m) with decreased deposition during the Middle Paleozoic, although thick clastic wedges built up on the interior side of the central and southern Appalachians. In Paleozoic times, convergence, and consequently orogenic activity, progressed from northeast to southwest. In the Ouachita segment, subsidence increased progressively through Mississippian to Mid-Pennsylvania times, leading to the accumulation of as much as 10000 m of clastic sediments. These turbidite deposits were derived from land areas to the southeast and east (Europe-Africa). Orogenic activity culminated in Late Pennsylvanian-Permian time.

The scene here shows the western end of the exposed Ouachita Mountains around McAlester in eastern Oklahoma, where mountains exceed 800 m in elevation, and local relief may be up to 500 m. The northern edge of unconformably offlapping Cretaceous sedimentary units, which dip south, abruptly obscure Ouachita structure along the southern edge of the mountains. These Cretaceous rocks also bury the eastern section, the Ardmore basin, of the Wichita aulacogen.

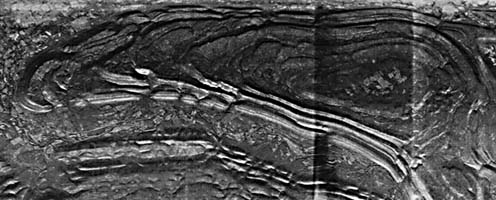

| Figure T-14.1 |

|---|

|

The structure across the Ouachitas, beautifully etched out by differential erosion, resembles the deformation patterns of the southern Appalachians (Plate T-11 ). Several major faults are named in the index map. A series of thrust sheets carry Mississippian and Pennsylvanian units, usually over younger beds. Traces of the thrust faults that join sole faults at depth are especially evident. One major thrust detachment overlies Lower Paleozoic rocks; elsewhere, these units are brought to the surface by folding. Spacing between individual imbricated sheets is greater to the south and decreases to the north in the Pennsylvanian units southeast and east of McAlester. The Upper Paleozoic strata are strongly folded (with some overturning) within each sheet, giving rise to closed plunging anticlines (A) and synclines (B and C). Most of the linear ridges associated with folds and thrusts are resistant units of the chert-bearing Pennsylvanian Jackfork formation. The Potato Hills are an inlier of Devonian rocks exposed probably as a fenster through a thrust sheet on an anticlinal node. Cambrian/Devonian rocks, including ridge-forming cherts, also crop out around Broken Bow Lake and form an extensive central core to the anticlinorium in the Arkansas section of the Ouachitas.

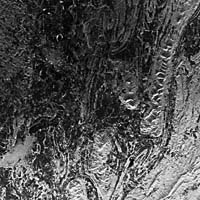

| Figure T-14.2 |

|---|

|

North of the Choctaw thrust, the structure changes to a synclinorium with gentler, more open folds developed in the Atoka, Stanley, and Jackfork shales and sandstones of Pennsylvanian age. There, in the Arkoma basin, the Arkansas River valley follows the general east-west trend of the fold axes. Both folding and faulting decrease northward as this section of the Ouachitas gradually merges with the homoclinal south flank of the Boston Mountains. Relief also diminishes, but some mountains still exceed 700 m in elevation.

Topography is similar to that of the folded Appalachians with homoclinal and generally linear ridges, but curved around plunging noses. Although it is difficult to determine dip on homoclinal ridges in the anticlinorium because of steepness of dip, scarp and dip slopes are more easily determined in the gentler folds. Trellis drainage is prevalent with subsequent strike valleys and crosscutting water gaps. Many ridges are breached at faults, manifested by offsets of the ridge line. These details are apparent in a real aperture airborne radar image (Figure T-14.1) and a Seasat SAR image (Figure T-14.2) of an area in Arkansas to the east. (NMS) References: Cebull and Shurbet (1980), Keller and Cebull (1972), King (1977), Thornbury (1965, Ch. 15), Viele (1973). Landsat 1146-16300-7, December 16, 1972.

Continue to Plate T-15| Chapter 2 Table of Contents| Return to Home Page| Complete Table of Contents