|

|

|---|---|

| Plate T-19 | Map |

|

|

|---|---|

| Plate T-19 | Map |

This low-Sun-angle scene, which straddles the Mexican states of Coahuila and Nueva León, depicts graphically the prominent structural features associated with the Sierra Madre Oriental. The Sierra Madre Oriental in this region is an excellent example of the wrinkled-rug style of décollement folding produced above a relatively shallow detachment zone. This orogenic belt represents the easternmost extension of the North American Cordillera. In Mexico, the Cordillera divides into the western Sierra Madre Occidental and the eastern Sierra Madre Oriental, separated by the southern extension of the Basin and Range and the Central Mesa before joining with the Sierra Madre del Sur, which then passes into the Central American orogenic belt. The Sierra Madre Oriental trends northwest over most of its length, but splits abruptly in this scene into a western branch and the Cross Ranges, then northward to rejoin the trend in the Basin and Range section.

The scene contains Jurassic to Cretaceous age rock units and younger basin fill. Paleozoic rocks presumably underlie the exposed Mesozoic units. After limited Triassic sedimentation (mostly in grabens), this region gradually submerged as the Atlantic opened to form the Mexican geosyncline, which ties into the depositional troughs of the U.S. Cordillera to the north. The eugeosyncline lay to the west (roughly where the Sierra Madre Occidental exists today) of the miogeosynclinal zone now occupied by the Sierra Madre Oriental. Deformation (thrusting and gravity slide folds) affected the eugeosyncline in Jurassic times, even as the present Gulf of Mexico began to open up to the east. Molasse sedimentation characterizes Jurassic deposits in eastern Mexico. By Mid-Cretaceous, marine waters had inundated most of Mexico, depositing carbonates (including reef units) and evaporites. Metamorphism and uplift of the eugeosyncline (Baja California region) in the Late Cretaceous provided coarser clastics carried eastward as flysch that spread over the shallowing miogeosyncline. The scene lies athwart a broad foreland basin that filled with clastic and carbonate rocks from the Jurassic to Early Eocene. The Eocene Hidalgoan orogeny, coeval with the late phase of the Laramide orogeny, produced the folds and thrusts evident in this image. Graben faulting followed, with flysch deposits accumulating in the structural basins while molasse clastics spread over the eastern coastal plains into the Gulf.

| Figure T-19.1 | Figure T-19.2 |

|---|---|

|

|

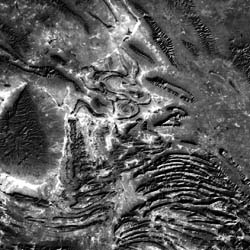

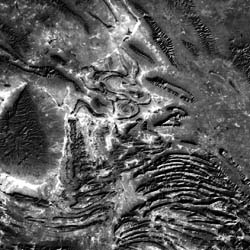

Several structural styles are discernible in this scene. Differential erosion has etched out less resistant rocks, leaving resistant ridges that outline the folds. Synclinal noses are broad arcs; anticlinal noses are sharper and longer. Many breached anticlines are evident. Gentler dipping synclinal beds show scarp and dip slopes. South of Monterrey is a belt of tight folds, part of an anticlinorium, dominated by east-west anticlinal mountains (up to 3500 m high) composed of predominantly limestone units that dip steeply in exposed vertical to overturned folds (Figure T-10.1 and Figure T-19.2, a vertical aerial and a ground photograph, respectively). These structures are made up mostly of Lower Cretaceous rocks with Jurassic rocks exposed in breached plunging anticlines and Upper Cretaceous rocks in intervening synclines. To the west, the Parras basin, which extends from Saltillo westward beyond the image, contains Upper Cretaceous sandstones and carbonates that form ridges whose outlines define open plunging synclines. Even broader synclines (Figure T-19.3) are found in the Paredon basin (Plate image center). The main belt of the northwest-trending folds in the Sierra Madre Oriental spreads across the top of the image. Most of the individual mountain units are anticlinal. Erosion has breached several (e.g., S. del Fraile) of these to varying extents. Sierra de Minas Viejas and others have Jurassic units exposed in their cores as salt-gypsum evaporite beds. The Sierra de La Paila is a broad domal arch of Lower Cretaceous rocks over a Tertiary intrusion.

| Figure T-19.3 |

|---|

|

Conjecture abounds on the reason for the deflection of fold trends in this part of Sierra Madre Oriental. Although the style of folding around Saltillo, Monterrey, and Paredon is clearly that of décollement , the underlying cause of the deflection is unclear. Several factors may have played a role, including gravity sliding off uplifted basement blocks, the distribution of evaporite units in the area, and, possibly most important, movement on the west-northwest-trending Torreon/Monterrey fracture zone. This left-lateral fault system that developed in the Early Mesozoic may have influenced distribution of the evaporite basins and controlled the deflection of the fold trends. Regardless of origin or mechanism, the resulting structures in this scene make up one of the most striking displays of tectonic landforms anywhere on the North American continent.

Figure T-19.1 is a vertical air photograph of the area south of Monterrey that shows the near vertical ridge of Cretaceous limestones. The syncline is ringed by outfacing scarps. Rivers anomalously cut across the structure. Figure T-19.2 highlights some of these ridges in the Huasteca Canyon area. Figure T-19.3 is a vertical aerial photograph of the small basin to the east-northeast of Paredon and shows the spectacular degree to which differential erosion has etched out the complicated structure of this arid area. (NMS) References: Baker (1971), McBride et al. (1974), Mitre-Salazar (1981). Landsat 1508-16410-6, December 13, 1973.

Continue to Plate T-20| Chapter 2 Table of Contents| Return to Home Page| Complete Table of Contents