|

|

|---|---|

| Plate T-2 | Map |

PLATE

T-2

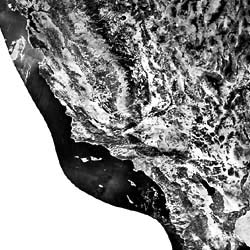

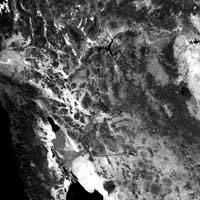

SOUTHWESTERN UNITED STATES

|

|

|---|---|

| Plate T-2 | Map |

The striking differences in topography within this area of southern California and Nevada damatically reflect the region´s tectonic provinces. This mosaic of Landsat MSS imagery displays the regional relationships among the San Andreas fault (an active transform fault boundary between the Pacific and North American plates), the Great Valley (a forearc basin), the Sierra Nevada (an old volcanic arc), and the Great Basin (an extensional province).

Over much of this area, the physiography is the direct result of tectonic processes, with resulting landforms only slightly modified by erosion. In the Coast Ranges, the Great Valley, and the Basin and Range, much of the relief is the result of deformation rather than erosion.

The Sierra Nevada consists of the roots of an ancient (Jurassic) volcanic arc that was similar to the present Andes of South America. The Sierra formed as a volcanic arc above the Pacific plate as it descended beneath the western edge of the North American plate in Jurassic time (Schweickert, 1981). Resistant rocks of the Sierras stand high (approximately 3000 m) above the adjoining geomorphic provinces. Jurassic and Cretaceous Franciscan mèlange rocks that accumulated in the trench west of the Sierra Nevada and serpentine that mark old sutures underlie the Great Valley (San Joaquin and Sacramento valleys) and much of the Coast Ranges. Fragments of Sierran rocks that have moved northward along the San Andreas and related faults underlie other parts of the Coast Ranges.

The Cretaceous and Tertiary rocks of the Great Valley sequence that comprise the fill in the San Joaquin Valley accumulated in a forearc basin west of the Sierran Arc and are deposits of debris eroded from the rising Sierras. Stresses related to plate convergence and subsequent right-lateral transform movement have produced several large folds and numerous faults that constitute traps for hydrocarbons within the Great Valley.

The northwest-trending linear fabric of the Coast Ranges results from a large strike-slip fault zone. One can trace the San Andreas system from the Gulf of California to Cape Mendocino, a distance of almost 1400 km. The aligned pattern of linear ridges and depressions separate markedly different terranes (the Great Valley to the east and the Coast Ranges to the west; see Plate T-3). Just north of Los Angeles, the topographic trace of the leftslip Garlock fault is evident, branching eastward from the San Andreas fault (Allen, 1981; Atwater, 1970; Dickinson, 1977). Figure T-2.1 shows intricately dissected topography developed on recently uplifted terrain adjacent to the San Andreas fault near Palm Springs.

| Figure T-2.1 | Figure T-2.2 |

|---|---|

|

|

This mosaic shows the pronounced linearity of the San Andreas fault in central and southern California, which marks the southern boundary of the Mojave Desert Basin. This fault is shown in more detail in a remarkable aerial photograph mosaic (Figure T-2.2), which required more than 8000 individual reprocessed large-scale aerial photographs to cover about the same area as a single Landsat image.

The San Andreas fault system is an active transform boundary between the Pacific plate to the west and the North American plate to the east. This fault system is a ridge/ridge transform that connects the north end of the East Pacific Rise in the Gulf of California and the south end of the Juan de Fuca Ridge off the coast of Oregon. The Pacific plate is moving northwestward (at about 2.5 cm per year) relative to the Northern American plate. As the Pacific plate moves northwestward, a gap (actually a new ocean basin similar to the Red Sea) is forming between the two plates (Atwater, 1970). The Salton Sea (the large lake) and the Gulf of California (the body of water at the bottom center of Figure T-2.3, a daytime visible band image made from the Heat Capacity Mapping Mission (HCMM) sensor) occupy this gap. Figure T-2.4, an oblique Apollo photograph of the Salton Sea, distinctly shows the scarp that marks the linear eastern edge of the Salton trough and the merging of both margins with the San Andreas fault to the north.

| Figure T-2.3 | Figure T-2.4 |

|---|---|

|

|

To the east of the Sierra Nevada is the Basin and Range (Great Basin) province, one of the largest areas of regional extensional tectonics on Earth. In the near-surface Tertiary, Mesozoic, and Paleozoic rocks, high-angle normal faults accommodate the extension. Extension exceeds 100 percent over most of the province (i.e., the region is about twice as wide as it used to be (Zoback et al., 1981).

The Coast Ranges T-3), the Great Basin (T-4), and Death Valley (T-5) Plates discuss specific portions of this area in substantially more detail and include additional illustrations. The Rocky Mountain Plate (T-6) discusses the area east of the Great Basin. (JRE) Additional References: Burchfiel and Davis (1975), Ernst (1981), Smith and Eaton (1978). Landsat Mosaic.

Continue to Plate T-3| Chapter 2 Table of Contents| Return to Home Page| Complete Table of Contents