|

|

|---|---|

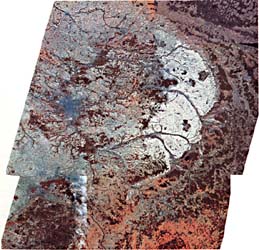

| Plate T-24 | Map |

|

|

|---|---|

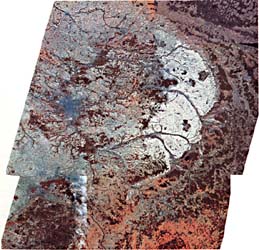

| Plate T-24 | Map |

Differential erosion of gently dipping (1 to 10°, layered rocks produces cuestas (long gentle dip slopes and steep scarp fronts). Mild deformation sets the stage for development of most cuestas. However, primary depositional dips can also produce cuestas where resistant beds lie between more easily eroded ones.

One of the best-known examples of a stratigraphic cuesta is the series of outward-facing scarps that rim the eastern and southern flanks of the Paris Basin in northeast France (Joly, 1984). This color mosaic illustrates a striking pattern of wide bands, roughly concentric, comprising valleys or low plains cut on less resistant rock and more resistant units marked by topographic rises with outfacing scarps or "côtes" (Figure T-24.1). Sinuosity of the cuestas is a result of gentle folding. Rivers cross the structure without regard to lithology, indicating probable consequent rivers that are antecedent or superimposed on the structure. Drainage adjustment has taken place as shown by wind gaps and river capture. For example, the Seine has captured the headwaters of the Meuse. Epeirogenic uplift has caused incision of river channels to fix them in their paths. To the northwest and west, the drainage has resulted in inverted relief as anticlines eroded.

| Figure T-24.1 | Figure T-24.2 |

|---|---|

|

|

The Paris Basin is a crudely oval feature of about 140000-km2 area with a long axis of nearly 400 km. Much of the area consists of flat valleys and low plateaus lying less than 100 m above sea level; eastward toward the Meuse, elevations reach 350 to 400 m, with relief generally less than 100 m.

The Paris Basin is an epicontinental depocenter developed on a continental shelf invaded by marine seas from time to time. It is built on a crystalline basement downdropped relative to surrounding crystalline highs of Hercynian age, chief of which are the Massif Central (south), Massif Armoricain (west), Massif Ardenno-Rhenan (northeast), and the Vosges (southeast) (Anderson, 1978). Marine sedimentation began in the Permian and continued into the Tertiary (L = Lias; MJ = Mid-Jurassic; UJ = Upper Jurassic). As many as six côtes or cuestas are developed on resistant Jurassic sandstones and limestones. Subsidence decreased somewhat in the Lower Cretaceous (LK), but by Upper Cretaceous (UK), the Tethys Sea to the south had transgressed and covered much of France. (Brunet and LePichon, 1982). The extensive chalk deposits (The Chalk) that outcrop in the Champagne Valley and westward in a ring passing through Amiens, Beauvais, and Chartres mark this transgression. Following a period of subaerial erosion, more episodic encroachments occurred in the Paleogene, with widespread Eocene (Eo) beds overlain by Oligocene and Miocene (Ol-Mio) units, a sequence of sands, marls, and clays preserved in the Valois, Brie, and Beauce plateaus near Paris.

Basement faulting has propagated to the surface, although displacements are not large. Several northwest-trending folds extend from the basin toward the English Channel. The Bray anticline, seen in the mosaic as a cigar-shaped pattern defined by vegetation (reddish), is erosionally breached with inward-facing scarps. Both structural benches and fluvial terraces attest to periodic rejuvenation in response to uplift in the Cenozoic. The Alpine orogeny to the southeast increased stream gradients. Man's clearing of the forest in postglacial time has disturbed the erosion/sedimentation balance of the rivers.

Figure T-24.2 and Figure T-24.3 show two other examples of landforms developed on gently dipping rocks. In the Mariental district of Namibia (Figure T-24.2), the Nama Group (Early Paleozoic) of sedimentary rocks dip at 1 to 5° eastward off a basement block (lower left corner) (Furon, 1963). Shales interbedded with quartzites (center left) form a distinctive pattern of swirls and contortions even though the units are not strongly deformed. Broad bands of the Schwartz Rand and Fish River Formations occupy the center third of the image; darker bands are more argillaceous than the lighter (sandstone) bands. A gentle fold (lower center), breached by an incised stream, causes local dip reversals. Karroo rocks lie unconformably (right in image) on the Nama Group, abruptly terminating the bands along the north side. Calcrete units holdup the scarp-bounded plateau (right and top). Windblown sand deposits, including longitudinal dunes, occupy the right corner.

| Figure T-24.3 |

|---|

|

Figure T-24.3 examines the west coast of the central Malagasy Republic (Madagascar). Precambrian crystalline rocks (Tananarive block) underlie about three-fourths of the island (Besairie, 1971). A major north-northwest-trending fault juxtaposes the massif (upper right) against Karroo sediments. A broad valley, drained by the Manambolo River, flows across the Isalo Group (Upper Triassic/Lias). This river then cuts through an upland of Jurassic sedimentary rocks and across a valley containing mainly Cretaceous limestones. The eastern front of the upland is an erosional scarp; another fault controls its western margin. North of the river, a dark band of rocks represents a higher plains unit formed from a sheet of Cretaceous basalt. To the west, this westward-dipping sequence includes sediments of uppermost Cretaceous rocks. (NMS) Landsat Mosaic.

Continue to Plate T-25| Chapter 2 Table of Contents| Return to Home Page| Complete Table of Contents