|

|

|---|---|

| Plate T-37 | Map |

|

|

|---|---|

| Plate T-37 | Map |

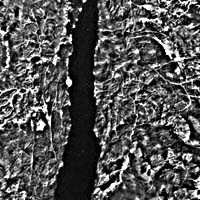

The Plate, an oblique photograph taken from Apollo 7, clearly illustrates the division of the Red Sea at its northern end into two linear depressions flanking the Sinai Peninsula. These depressions, the Gulf of Suez and the Gulf of Aqaba, and the Red Sea itself are products of active tectonism. About 40 Ma ago, Arabia was an integral part of the African continent, but by Late Oligocene time, rifting had begun along the future site of the Red Sea. This rifting resulted in the formation of the Arabian plate that broke away from the African plate and began to move northward independently (see Plate T-36).

An active spreading center in the axis of the Red Sea joins another in the Gulf of Aden at the Afar junction where the East African Rift extends southward into the continent. Separation of the two plates is greater in the south along the Red Sea, and true ocean floor does not extend all the way to the Gulf of Aqaba.

The Gulf of Suez is 30 to 50 km wide compared to over 160 km for the northern Red Sea. The trend of the Gulf of Suez is the same as that of the Red Sea; it can be thought of as an extension of the Red Sea Rift. The Dead Sea fault system is an active left-lateral strike-slip fault with local extensional and compressional segments. Cumulative displacement of a little over 100 km since the Miocene has been reported (Freund et al., 1970).

About 40 Ma ago, a large area in northeastern Africa and the Arabian Peninsula was covered by seas, and thick limestones were deposited. As rifting progressed, the shoulders of the rift, not only along the Red Sea but also along the Gulf of Suez and much of the Dead Sea transform fault, were elevated several kilometers. Garfunkel and Bartov (1977) report as much as 4 km of vertical displacement along faults in the Sinai near the southern end of the Gulf of Suez. Intensive erosion of these uplifted areas removed the sedimentary cover, exposing the underlying crystalline rock. These are the dark-toned highly fractured areas seen in the Plate and Figure T-37.1, a Landsat view, on the southern end of the Sinai Peninsula, along the Gulf of Aqaba and adjacent to the Red Sea and Gulf of Suez. Relief in these rugged highly dissected areas exceeds 2000 m at Gebel Muss (Mt. Sinai) near the center of the crystalline rock outcrop in Sinai. An adjacent peak, Gebel Katherina, is more than 2500 m high. Elevations on the west side of the Gulf of Suez are much lower. Gebel Gharib, near the northern end of the dark zone, is less than 1800 m high.

| Figure T-37.1 | Figure T-37.2 |

|---|---|

|

|

Uplift of the border area along the Gulf of Suez was not uniform, but diminished northward, thus preserving Tertiary and older sedimentary rocks around the northern end of the Gulf, and in the interior of the Sinai Peninsula. The lighter toned areas on each side of the Gulf of Suez are Miocene sediments dropped down on normal faults and preserved. These rift shoulders are partly covered with erosional debris from the mountains deposited as alluvial fans and wadi channel fill. Figure T-37.2 shows the abrupt topographical contrast between Miocene and Quaternary sediments and crystalline rocks that form the rift walls.

Although the topographic features adjacent to the rift are impressive, those under water are equally spectacular. As extension progressed in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Suez, deep chasms formed, and large elongate blocks broke from the adjacent walls and slumped into the void, Some blocks are several kilometers long and a few kilometers wide. As extension continued, the bottom of the rift subsided, mainly in response to sediment loading, by as much as 5 or 6 km in the Gulf of Suez (Bayoumi, 1983) and by even more in the Red Sea. Topographic differences in the rift bottom never approached these values because slump blocks and erosional debris from the adjacent landmasses partially filled the depression as it subsided.

| Figure T-37.3 | Figure T-37.4 |

|---|---|

|

|

The Gulf of Aqaba can be considered a complex of pull-apart grabens associated with the great Levant transform fault that extends well to the north of the Dead Sea (Plate T-38). Erosion along the uplifted margins of the Gulf has produced a number of deltas, which line the shore (Figure T-37.3). The faulting associated with this graben system can be seen in the Plate image as straight lines extending from the Gulf of Aqaba to the Dead Sea. The graben is complex in that the surface does not consist of a single down-dropped block, but is cut by numerous cross faults. A topographic high creates a drainage divide near Gebel el Khubeij. From this point both northward and southward, elevations drop to below sea level. Several isolated deeps have been mapped in the Gulf of Aqaba, and one, located about midway along the Gulf, is more than 2000 m below sea level. The Dead Sea (Figure T-37.4, near Wadi ah Arabah) represents another major pull-apart graben along the strike-slip fault. The water surface is approximately 400 m below sea level, and water depths exceed 300 m in places. Sediment fill in the Dead Sea is several kilometers thick. The linear edge of the graben between the Gulf of Aqaba and the Dead Sea is quite evident in the Plate and Figure T-37.1. Sediments are being poured into the graben from both sides, forming fans and bahadas. The distinctive uplands terrain, a dissected plateau, east of the fault valley in Jordan (upper right corner of Plate image), is depicted in Figure T-37.4 (Ordovician sedimentary rocks near Mahattat al Mudawwarah). (GCW: O. R. Russell) Additional References: Bartov et al (1980), Ben-Avraham et al. (1979), Coleman (1974), Eyal et al. (1981), Garfunkel (1981), Garfunkel et al. (1981), Quennell (1958). Apollo 7 7-5-1623.

Continue to Plate T-38| Chapter 2 table of Contents| Return to Home Page| Complete Table of Contents