|

|

|---|---|

| Plate T-43 | Map |

|

|

|---|---|

| Plate T-43 | Map |

The mosaic on pages 128-129, made up of more than 130 individual Landsat scenes, displays the morphology associated with large-scale crustal deformation along the western end of the continental collision belt across southwest Asia (Stocklin, 1974). The mosaic includes all of Pakistan, most of Afghanistan, and parts of Iran, Oman, the U. S. S. R., India, and China. During the Late Paleozoic, the southern continents were gathered together as the Gondwana supercontinent. The south Asian section of Gondwana broke up in two stages during the Mesozoic. First, a small slice known as the Cimmerian continent split off in the Permo-Triassic and moved north to collide with previously accreted Asia in the Mid-Jurassic, leaving the Paleo-Tethys seaway in its wake. Then, about 130 Ma, India broke away from eastern Gondwana and began to drift north toward Asia. As the Paleo-Tethys was consumed in front of India, the Neo-Tethys was formed behind it. Their ancient ocean crusts are now recorded by ophiolites and related rocks along suture lines between continental fragments. Major tectonic features associated with these collisions are located on the index map inset on the mosaic.

| Figure T-43.1 | Figure T-43.2 |

|---|---|

|

|

This mosaic might well be subtitled "the suturing of microcontinents." The tonal patterns clearly discriminate between relatively stable areas and deformed orogenic belts. On the north are the Tarim and Turpan platforms, which were intruded by Triassic batholiths that formed beneath island arcs in the north Paleo-Tethys. To the south is the Indian subcontinent, and to the southwest is a corner of the Arabian Peninsula, each with obducted ophiolites on its northern edge. In between are fragments of the Cimmerian continent: the Lut and Dasht-I-Margo/Afghan blocks to the west, the Lhasa block to the east, and an unnamed, poorly known block north of the Main Karakoram Thrust and south of the Pamirs. Ophiolites (shaded patterns on the index map) along the Neh fault, on the Kabul block, and along the Karakoram fault mark the edges of these microcontinents.

The cores of these blocks, platforms, and continents have been little affected by the collision, whereas areas between them are intensely deformed. The northern suture with remnants of the Paleo-Tethys extends from northern Iran, along the Helmund fault, through the Pamirs, and on to east along the North Tibet suture. The southern suture lies in two bands across the western portion of the mosaic. One is seen in Oman and then along the northwest edge of the Kirthar/Sulaiman Ranges. The other borders the Murien depression, passes through the Ras Koh, and continues along the southern edge of the Kabul block. These two bands are separated by deep marine sediments (flysch) present in the Makran Ranges and between the Chaman and Ghazaband faults (Figure T-43.1, an Apollo oblique photograph looking north across the Makran along the faults). These faults join together in the intense collision zone north of India along the Main Mantle thrust and the Indus suture.

| Figure T-43.3 | Figure T-43.4 |

|---|---|

|

|

The Cenozoic collision of the Indian subcontinent with Asia about 50 Ma ago caught the Cimmerian blocks in a tectonic vise, creating crustal compression with both convergent and lateral components. Between 20 Ma and the present, continuing northward movement was accompanied by clockwise rotation of the Indian subcontinent, leading to the formation of the Himalaya Mountains rimming India on the north, the Hindu Kush ranges to the northwest, and the highly deformed suture zone between the Dasht-I-Margo and Indian platforms.

The images on the next page and the three Plates (numbered on index map) that follow illustrate deformation typical of the western collision zone. A Landsat view (Figure T-43.2) of the Kirthar Range (A on index map) focuses on highly deformed Tertiary and Upper Mesozoic carbonate and clastic rocks east of the Oranach-Nal fault (just off left edge of the scene) that separates these units from imbricated north-dipping thrust sheets of flysch sediments in the Makran Range where it swings northward.

| Figure T-43.5 | Figure T-43.6 |

|---|---|

|

|

Figure T-43.3, another Landsat image (B on index map), concentrates on the Chaman fault, which trends north near the left edge. This fault extends from near Kabul in Afghanistan, thence some 900 km south-southwestward to the northern edge of the Makran Range. Movement along the fault in 1892 offset the Quetta-Chaman railroad 75 cm in a left-lateral sense, the consequence of continuing northward movement of the Indian subcontinent. West of the fault are darker volcanic rocks in the eastern extension of the Ras Koh Mountain Range. Similar rocks appear again at the north edge of the image just west of the Chaman fault. Slaty cleavage is well developed in the mountainous terrain east of the fault, with the tectonic fabric of the entire range being controlled by stresses that produced the fault. The Ghazaband fault lies within the right half of the image; on the west side are the folded flysch units caught in a shear couple between the Chaman/Ghazaband faults, and to the east are Indian plate shelf beds.

| Figure T-43.7 |

|---|

|

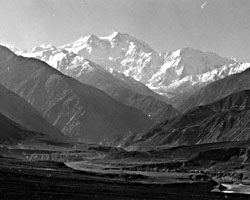

The remaining four photographs on the facing page give a sense of the rugged terrain and structure of the mountain country of Pakistan. Figure T-43.4 looks south along the Chaman fault about 35 km south of the town of Nushki. The fault runs from the lower left to the top center of the photograph. Looking east across this fault (Figure T-43 .5), one can see the Khojak hills (Eocene and Oligocene) in the distance and the low ground of the fault zone itself in the middle ground. Pliocene/Pleistocene sediments from the Ras Koh occupy the foreground. Anticlines and synclines (Figure T-43.6) outlined by differential erosion lie just west of the Chaman fault zone and are large-scale drag features in the rocks of the Makran. Figure T-43.7 is a view south along the Indus River near the mouth of the Astor River looking toward Nanga Parbat, a peak typical of the Hindu Kush. The valley is occupied by the active Raikot fault. This picture also includes glacial terraces along the river; in this tectonically active area, there are folds in Pleistocene to Recent glacial till with overturned limbs. (GCW: R. L. Lawrence; J. D. Dykstra) Additional References: Andrieux and Brunei (1977), Farah and DeJong (1979), Farah et al. (1984), Gansser (1980), Lawrence et al. (1981), Molnar and Tapponnier (1977), Sengor (1979, 1984), Stoneley (1975), Yeats and Lawrence (1984). Landsat Mosaic.

Continue to Plate T-44| Chapter 2 table of Contents| Return to Home Page| Complete Table of Contents