|

|

|---|---|

| Plate C-7 | Map |

|

|

|---|---|

| Plate C-7 | Map |

The southwest corner of Ireland is the classic example of an Atlantic type of continental margin, with the coast cutting obliquely across the Hercynian (Appalachian) orogenic trends and breaking the strike ridges of Paleozoic rocks. Somewhere in eastern North America, perhaps covered by Mesozoic and Cenozoic continental shelf sediments, these same strike ridges resume, torn apart by the Mesozoic rifting and opening of the Atlantic Ocean basin. The straight northwest-southeast alignment of the ends of the peninsulas is parallel to the faulted margin of a Tertiary basin about 20 km offshore (Stephens, 1970, p. 134).

Relatively few islands extend from the tips of the peninsulas, showing that the Paleozoic fold axes plunge so steeply that, within a few miles after they enter the sea, they are completely submerged. Similarly, the bays between the headlands are deep and open, although wave energy in them is quickly damped by refraction.

| Figure C-7.1 | Figure C-7.2 |

|---|---|

|

|

The Armorican Highlands of southwestern Ireland lie south of a line extending east from the head of Dingle Bay. They were lightly glaciated by a small ice cap, not part of the Fennoscandian ice sheet or the late-glacial Scottish ice cap. Ice flowed down the structural valleys to the sea, but did not create distinctive glacial troughs. Some drumlins in the glaciated valleys are now islands. Near present sea level, the slopes were subjected to intense periglacial frost action and mass wasting. Thick deposits of periglacial solifluction debris, angular rock fragments mixed with silt and clay, cover the lower valley walls. This "head," as it is locally known, gives a smooth rounded aspect to the landscape, although ridge crests tend to be rugged with tors, residual masses of bedrock that have been exposed by downhill solifluction as at Hag's Head, south of Galway (Figure C-7.1 and Figure C-7.2). The area has been deforested by grazing and woodcutting, and erosion is severe. Peat bogs or lakes fill many of the small depressions, and peat "blanket bogs" mantle many of the gentle lower valley walls.

Ancient abrasion platforms are found at various places this coast, some submerged and some emerged by amounts ranging from 3 to 9 m (Stephens, 1970, p. 140). Their age is uncertain, but they are generally being exhumed from beneath glacial drift or the periglacial "head." Their height has led to much speculation about the extent of postglacial isostatic uplift in the region and, thereby, the inferred thickness of the former ice cap on the mountains. If these shore features formed during last interglacial time, when the sea was a few meters higher than at present (see Plates C-2, C-4, and C-14), they may not have been significantly displaced.

| Figure C-7.3 | Figure C-7.4 |

|---|---|

|

|

Wave energy along this coast is refracted by the deep embayments. The small subsequent rivers follow the southwest-plunging strike valleys and enter the bays at their extreme inner ends. The wide flaring estuaries focus waves and currents to build some remarkable straight long tombolos and spits near the heads of bays, especially in Dingle Bay. These are among the few coastal depositional features to be seen on the image. The coast is a rather simple example of a fluvial landscape that was eroded on the strike ridges of an ancient mountain belt and was then torn apart and submerged (Figure C-7.3).

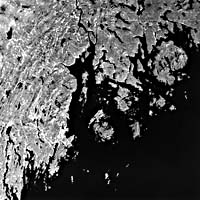

Very similar topography can be seen in the Landsat subscene of the Penobscot Bay region of the State of Maine (Figure C-7.4). Although that area was glaciated, the lineation is primarily of bedrock strike ridges. Neither Ireland nor Maine has fjords. Rather, these are rias or strike-controlled river valleys. Landsat 2573-10492-6, August 17, 1976.

Continue to Plate C-8| Chapter 6 Table of Contents.| Return to Home Page| Complete Table of Contents|