|

|---|

| Plate E-27 |

|

| Map |

|

|---|

| Plate E-27 |

|

| Map |

This color mosaic contains a portion of the Tarim Basin in western China, one of the largest internal drainage basins in the world. The elliptical-shaped basin is bordered by the Tian Shan on the north and the Kunlun Shan and Altun Shan on the west and south. Parts of those mountains are glaciated. The basin grades into the Inner Mongolian Plateau on the northeast, and toward the east into Lop Nur, the large playa shown on Plate E-25. The elevation at Lop Nur is 780 m, but the western Tarim Basin rises to about 1560 m. As seen in the mosaic, most of the intermittent streams with headwaters south of the basin flow north from the Kunlun Shan into the desert. Farther east are the two non-north-flowing rivers in the basin-the Qarqan River that rims the southeastern edge, and the Tarim River that flows east along the northern border; these rivers appear in Plate E-26.

Two distinct deserts occupy the Tarim Basin. The smaller (19 500-km2) Kumutage Desert east of Lop Nur is composed of gobi, sand sheets, and crescentic, linear, and star dunes 10 to 30 m in height. More than 100 km of Quaternary alluvium and marshland on the lacustrine plain of Lop Nur separate the Kumutage and the Taklimakan. With a total area of 3 37 600 km2, the Taklimakan Desert is the largest desert in China and one of the largest in the world. The name is derived from a minority language expression meaning "once you get in you can never get out." Gobi surfaces are located only along the southeastern and northern borders of the Taklimakan. Approximately 85 percent of the desert consists of moving sand dunes that average 100 to 150 m in height in the northeastern desert but locally maybe as high as 200 m. Dunes along the periphery of the desert and in its western reaches are only 5 to 25 m tall (Zhu et al., 1980). Crescentic, linear, dome, and star dunes are found throughout the Taklimakan.

| Figure E-27.1 | Figure E-27.2 |

|---|---|

|

|

Explorer Fa Xian described the Taklimakan in A.D. 400 by saying, "In this desert there area great many evil spirits and also hot winds; those who encounter them perish to a man. There are neither birds above nor beasts below. Gazing on all sides as far as the eye can reach in order to mark track, no guidance is to be obtained save from the rotting bones of dead men, which point the way" (Giles, 1923).

Through analysis of the heavy minerals in the sands of the Taklimakan, Zhu (1984) determined that much of the desert sand is a product of weathering of the bedrock from the bordering mountains. These materials were transported into the basin by water and deposited in floodplains and river beds. He associates the average size of the sands with the grain size of the underlying deposits, and notes that wind presently dominates the activity of the Taklimakan. Zhu (1984) discusses two dominant wind regimes. Northeasterly winds dominate much of the desert, but winds from the northwest dominate the western Taklimakan. These two wind systems meet in the central-west part of the desert, resulting in a complex dune alignment.

This mosaic covers the Kunlun Mountains and a southwest section of the Tarim Basin. The snowfield decreases on the lee side of the range. Several intermittent streams fed from the Kunlun flow into the desert. Note the red vegetation on the oases and alluvial plains at the foot of the mountain. Some of the vegetation extends into the desert for some distance.

| Figure E-27.3 | Figure E-27.4 |

|---|---|

|

|

Sand sheets and gobi are common west of the Yarkant River. The small streams in that area in the Plate flow east onto the plain. One of the alluvial fans has been breached, and a small second fan is being established on the northeastern end of the flank.

The Hotan River is formed by the joining of the Karakax on the west and the Ywungkax on the east. The Hotan is an exotic stream fed from the Kunlun. In the northern Tarim Basin, it merges into the Tarim River. The Hotan channel bed provides the only transportation system across the Tarim.

Note the extremely narrow 200-km long east- west range between the Hotan and the Yarkant Rivers. Its 100- to 300-m high escarpment is composed of red sandstone, shale, and gypsum. Because these beds dip toward the north, the south slope is steeper than the north. A map of the wind patterns in the Taklimakan indicates that the northeasterly wind pattern does not change direction when it passes over the range (Zhu et al., 1981).

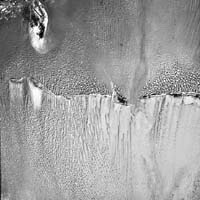

Figure E-27.1 is a digitally enhanced Landsat image that encompasses this range. The pileup of sand against the windward side of the range is noteworthy. The simple linear dunes in the upper right of the figure coalesce westward into complex linear dunes with crescentic dunes on their crests. Sand sheets followed by crescentic dunes concentrate in the west. The sand sheets, which cross a break in the escarpment, may represent a paleodrainage channel. Approaching the escarpment from the north, linear dunes merge into crescentic types. In the mosaic, it is evident that the simple linear dunes on the Yarkant River floodplain do not change their orientation as they cross the escarpment.

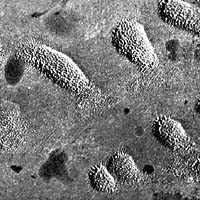

The dunes south of the escarpment illustrate the wind- shadow effect of this topographic barrier. Small dome dunes formed south of the escarpment, and as the distance from the escarpment increases, the domes begin to coalesce into complex linear dunes. This is more obvious below the western part of the escarpment because the Hotan floodplain has probably reduced the amount of sand. Figure E-27.2 depicts dome dunes of the Taklimakan. These dunes are described by Zhu (1984) as being 40 to 60 m tall with slipfaces approximately equal in length and width. As the figure illustrates, they are circular or elliptical in shape. Zhu states that dome dunes are irregularly distributed in the Taklimakan.

| Figure E-27.5 |

|---|

|

To the east, the two dominant wind directions in the Taklimakan Desert meet near the Keriya and Niya Rivers, resulting in a significant difference in dune types. The simple short linear dunes of the Hotan River floodplain grade into complex crescentic dunes and linear dunes. Note the wind- shadow effect of the small hills between the two rivers. It is easy to study the changing wind regime with the dune pattern.

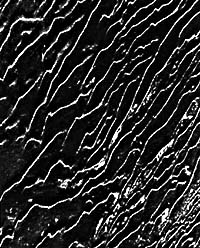

A compound crescentic dune typical of the Taklimakan is illustrated in Figure E-27.3. The direction of the wind points toward the bottom of the aerial photograph. As the horn narrows, the orientation of the superimposed crescentic dune does not change. The linear dunes in Figure E-27.4 are sometimes called fishhook dunes because many of them terminate in a hook. This is particularly conspicuous in bottom right of the figure. As illustrated in this Plate and in Plate E-26, linear dunes are one of the most widely distributed dune types in the Taklimakan (Zhu, 1984). Figure E-27.5 is an array of complex linear dunes with crescentic dunes superimposed both on the linear dunes and on the interdunal areas. These dunes are sometimes called scaled dune groupings or akle dunes because they resemble fish scales (Zhu, 1984). Landsat Mosaic.

Continue to Chapter 8 References| Chapter 8 Table of Contents.| Return to Home Page| Complete Table of Contents