|

|

|---|---|

| Plate V-13 | Map |

|

|

|---|---|

| Plate V-13 | Map |

The Galapagos Archipelago achieved fame in the l9th Century because its remarkable fauna played a key role in Charles Darwin's thinking on the evolution of living creatures (Darwin, 1844). These volcanic islands also impressed Darwin with their wealth of information on the nature of volcanism. His writings on the geology of this region are another monument to his profound insights.

The Galapagos are a cluster of islands lying along the Equator about midway (900 km) between the Ecuadorian coast to the east and the submerged ridge marking the spreading center of the East Pacific Rise (EPR) to the west (Durham and McBirney, 1975). The islands (highest point 1689 m) emerge from a basaltic base, the Galapagos Platform, that rises out of nearby oceanic deeps from -1200 to - 3500 m. This platform merges eastward into the Carnegie Ridge and lies at the southwest end of the northeast-trending Cocos Ridge. The islands are located just south of the east-west Galapagos Spreading Ridge (rate: 3 cm/yr). The volcanoes align along a northwest-southeast set of fractures; northeast-southwest fractures and an east-west s et al also exert some control over the distribution of eruption centers (Nordlie, 1973). Since their emergence more than 3 million years ago, the islands have been moving eastward along the spreading direction established at the EPR. The oldest volcanics are found in the center, whereas the youngest lie near the western margin. Petrologically, the extrusive are mainly tholeiitic and alkalic basalts of the oceanic type, with minor amounts of trachytes and pyroclastic basaltic tuffs (often altered to palagonite) (McBirney and Williams, 1969). The islands have been formed within a plate that has moved over a surface hotspot fed by a mantle plume, an origin analogous to the Hawaiian Islands. The Carnegie and Cocos Ridges are older now-submerged volcanic piles that resulted from the passage of the Cocos and Nazca plates over this plume.

| Figure V-13.1 |

|---|

|

The volcanoes on the western islands are among the most active in the world (39 eruptions since 1700 A. D.; Macdonald, 1972; see also Simkin, 1984). Seven days before this scene was imaged by Landsat, the Sierra Negra volcano, whose caldera is evident at (D), began to erupt. A light-toned streak (orange in a color composite) along the flank fixes the path of the main lava flow; a vapor cloud from this activity is also evident.

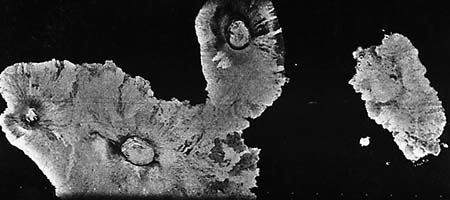

The scene also reveals nearly cloud-free glimpses of the major eruptive centers on the big island of Isabela (Albemarle Island as named by British explorers). Its J- shaped outline is closely allied to the northwest- and northeast-trending fault zones. Three of Isabela's large calderas are visible. The northernmost is the summit of Wolf Volcano that rises to 1710 m. The top is broad and relatively flat, but the upper slopes steepen to 35°. The central caldera measures 6 by 4.5 km and is more than 600 m deep. At least 10 eruptions since the late 1790s have been recorded there. A nearly circular (4.5 km diameter) caldera tops Darwin Volcano, along whose flanks are many lava flows emanating from both radial and concentric fractures. No historic eruptions are known from Darwin. Alcedo Volcano (1130 m) has erupted at least once during this century. Along the western shores of Isabela Island are the breached and down-faulted Ecuador Volcano (A) and the smaller tuff ring structures of Tagus Cone (B) and Beagle Cone (C). These were built by explosive (phreatomagmatic) action; most of the larger shield volcanoes on this island were generated from rather quiet effusive outpouring, but pyroclastic deposits on their upper slopes indicate occasional more violent eruptions at each. The two remaining large calderas, Sierra Negra (partly visible) and Cerro Azul (just off the image) are shown in Figure V-13.1, a SIR-A radar image taken from the Space Transportation System (Shuttle) in November 1981.

| Figure V-13.2 |

|---|

|

A single volcanic edifice, exceeding 1350 m in elevation, comprises Isla Fernandina (Narborough). Its gentle lower slopes (3 to 6°, steepen locally to 35° near its flattened upper bench. Extensive aa lava flows in all directions attest to repeated eruptions in the past few thousand years. The central caldera (Figure V-13.2) is elliptical (6 by 4 km). The lake shown in Figure V-13.2 was totally evaporated by a large eruption in 1958 (T. Simkin, private communication). Another eruption in 1968 led to collapse within the caldera, during which its floor dropped 350 m, and a new lake has developed, into which later lava flows have entered, including one just 15 months before the date of this Landsat pass.

Erosion of the islands results from a mix of surface water runoff (from rainfalls up to a maximum of 260 cm on Santa Cruz), ground-water action as rainwater enters porous basalts, and persistent wave action along the coast. Gully-forming erosion is especially active along surfaces covered by fine ash compacted to an impervious cover (e.g., around Beagle Cone). Text modified from comments by T. Simkin, Smithsonian Institution. Landsat 30624-15340-7, November 19, 1979.

Continue to Plate V-14| Chapter 3 Table of Contents.| Return to Home Page| Complete Table of Contents