|

|

|---|---|

| Plate V-5 | Map |

|

|

|---|---|

| Plate V-5 | Map |

This large-area mosaic includes nearly all of Oregon and Washington and part of Idaho and southernmost British Columbia. Graphically depicted are much of the Idaho/Montana Rocky Mountains and parts of the Canadian Rocky Mountains on the east and north, the Cascades and Coast Ranges to the west, and the northern boundary of the Basin and Range on the south. The Columbia Plateau and other volcanic geomorphic subprovinces within the mosaic are located in the index map. The region has recorded several extensive episodes of major volcanism during the Late Cretaceous and continuing throughout Cenozoic time (Christiansen and McKee, 1978; Armstrong, 1968).

In the Cenozoic, sections of the Pacific Northwest have been marked by an earlier predominance of calc-alkaline volcanism into the Miocene with a gradual transition in places to bimodal basaltic-rhyolitic magmas. The Western Cascades have remained calc-alkaline since Mid-Miocene. Volcanic eruptions have piled up as much as 1.8 km of lava and tephra in the northern Great Basin, Columbia Plateau, and Snake River depression, covering up lower altitude (mature) topography west of the Idaho Rockies and leaving a few structurally deformed higher Paleozoic/ Mesozoic mountain systems mainly in northern Oregon as projections above the general level.

| Figure V-5.1 | Figure V-5.2 |

|---|---|

|

|

The earliest Cenozoic was generally a volcanically quiet time in the region except for submarine basaltic activity in the ancestral Coast Ranges and the Olympic Mountains. Widespread igneous activity commenced in the Eocene over much of northern Idaho and Washington, spreading southward with plutonic intrusions and large-scale surficial volcanism that culminated in the Challis episode (50 to 43 Ma). This calc-alkaline volcanism extended from the Absaroka Mountains of northwest Wyoming into southwestern Montana, the central Idaho Rocky Mountains and southern British Columbia, central Oregon, and the proto-Cascades and Coast Ranges. Another episode of relative quiescence followed for nearly 20 Ma, but the Cascade volcanic arc began to take on its modern definition, and extensive volcanic ash and welded tuffs of the Oligocene/Miocene John Day Formation covered parts of the Blue Mountains/ Ochoco-Wallowa Mountains in northeast Oregon.

Cenozoic volcanism culminated in great floods of tholeiitic basalt, mostly during a brief interval from 17 to 13 Ma ago (90 percent in 1 Ma), centered on vents east of the Pasco Basin of central Washington, which continued to sag as the lavas were withdrawn. Successive flows, some up to 50 m thick (Figure V-5.1), spread from linear fissures over a wide area (presently, more than 400,000 km2), with concomitant bimodal eruptions in eastern Oregon indicative of the transition previously mentioned. In the last 13 Ma, volcanism has concentrated in the southern Oregon Idaho strip and the Cascades, principally during intervals from 10-8, 7-5, and 2 Ma to the Present. Much of the modern landscape around the volcanic centers evolved during these times. The period also witnessed extensional tectonics in the Great Basin (Basin and Range) to the south, high heat flow and crustal thinning, and subduction-controlled Cascade volcanism (stratocones superposed on shield volcanoes) as the Juan de Fuca/Farallon Plates continued to subduct under the North American plate.

| Figure V-5.3 | Figure V-5.4 |

|---|---|

|

|

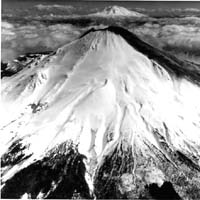

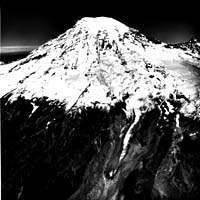

Volcanism continues today, although at a minuscule pace compared with some other segments of the Pacific Ring of Fire. On May 18, 1980, Mt. St. Helens (Figure V-5.2), one of the younger stratovolcanoes of the middle Cascades, blew its top (reducing its height by more than 300 m), after swelling for several months from upwelled magma. Triggered by a sudden failure of the summit's north slope, the volcano violently ejected great quantities of ash as a lateral blast. Other large stratocones, such as the Three Sisters in Oregon (Figure V-5.3) and Mt. Rainier in Washington (Figure V-5.4), have been sites of repeated activity in the last million years and are likely to be reawakened in the future.

From space, the landforms of the flatter sections of the Columbia Intermontane Province show few obvious signs of volcanism. The Columbia Basin is a region of moderate relief, fairly extensive soil cover, glacial erosion and aggradation, and loess deposition, largely masked by wheat farming and natural grass cover. Canyons caused by flood erosion (see Plate F-27) and coulees (now-abandoned fluvial canyons) offer some exposure of underlying lava units. Rugged, often spectacular terrain occurs within high country along the Snake River Canyon (in places more than 1500 m deep) and in the mountains of the Central Highlands. Not until the flows of the High Lava Plains (Plate V-7) are reached is a young volcanic terrain with many preserved primary features imposed on the landscape. Caption modified from comments by N. H. Macleod, USGS. References: Christiansen and Lipman (1972), Harris (1976), and Groh (196.5), Waters (1961). Landsat Band 5 Mosaic.

Continue to Plate V-6| Chapter 3 Table of Contents.| Return to Home Page| Complete Table of Contents