|

|

|---|---|

| Plate F-18 | Map |

|

|

|---|---|

| Plate F-18 | Map |

The Tian Shan is a series of east-west parallel ranges averaging 3000 m above sea level in extreme northwest China, Province of Xinjiang. The fold belt was generated in a Late Paleozoic orogeny. Sediments from Mesozoic uplift were shed into the Kucha sedimentary basin to the south. Renewed uplift in the Cenozoic produced the present dichotomy between the Tian Shan and the Tarim Basin that is evident on this Landsat scene.

The Tarim Basin is named for the Tarim River, which is fed by snow and glaciers of the Tian Shan, the Kunlun Mountains of northern Tibet, and the Pamirs of the China/Afghanistan/ U.S. S. R. border region. The river flows through a great inland basin, which includes the Taklimakan Desert (Petrov, 1976). Elevations average about 1000 m and drop eastward to 760 m at Lop Nur, the playa at the river's terminus, about 700 km east of this scene.

The Taklimakan has an arid continental climate with long cold winters and short hot summers. Continentality is achieved by its location in interior Asia and by near enclosure of the basin by some of the highest mountains on Earth. Although annual rainfall averages less than 100 mm, the flow of the Tarim River maintains riparian woodlands, as shown at the bottom center of the Landsat scene.

| Figure F-18.1 | Figure F-18.2 |

|---|---|

|

|

Melting snow of the Tian Shan supplies water to the piedmont surfaces north of the Tarim River. The piedmont is underlain by Mesozoic sedimentary rocks that are mantled by alluvial fans flanking the mountain front. The fans comprise a dark-toned bajada, which is made up of surfaces of varying ages, probably reflecting alternating episodes of incision and aggravation through the Quaternary. The adjustments may have been induced by climatic change, tectonic activity at the mountain front, or a combination of both. Younger fan surfaces are inset into older ones, which undergo weathering when they no longer receive active sedimentation. The old fan surfaces are dark on this Landsat image, probably because of the accumulation of desert varnish (mainly manganese oxides) on the coarse particles of the fan surfaces.

Several areas of irrigated farmland are located at distal sites on the Tian Shan alluvial fans. These areas have finer grained soils and more continuous water supply than the higher and proximal fan surfaces. Cotton is the dominant crop.

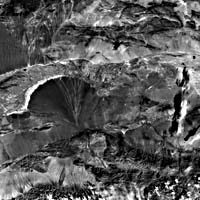

Figure F-18.1 shows another Chinese alluvial fan. The fan is shown on another Landsat scene (2621-03235-6, October 4, 1976). This fan is derived from flows out of the Qilian Shan Mountains at the bottom of the image. The fan occurs in Gansu Province, approximately 500 km east of Lop Nur. As with the Tian Shan fans, the active drainage has entrenched older, darker fan surfaces.

| Figure F-18.3 |

|---|

|

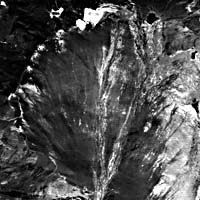

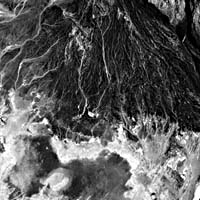

Figure F-18.2 shows the Ruo Shui River in the western Badain Jaran Desert, which feeds one of the largest known alluvial fans in the world. The river originates in the Nan Shan Ranges to the south and drains into the Badain Jaran Desert. The entrenched alluvial fan shown in Figure F-18.3 lies on the south slope of the Hajar Range (Oman Mountains) located on the eastern side of the Arabian Peninsula. The dark tone of the alluvial slope is produced largely by desert varnish coating chert fragments. This is no longer a plain of accumulation and is now being eroded by water and wind action. The toe of the fan has been completely removed, exposing lighter toned Tertiary strata.

The causes of fan entrenchment, producing the abandonment of old fan surfaces, remain the subject of considerable debate among geomorphologists. Classic observations in the Gobi Desert by Huntington (1914) led to the hypothesis that high sediment production and low stream discharges resulted in aggravation during relatively dry climatic phases. This was then followed by downcutting when wetter climates led to the stabilization of slopes by vegetation. During wet phases, called "pluvials," streams with increased flow augmented their sediment load by bed incision. Alternatively, some geomorphologists in the western United States have argued that fan-building required a wetter climate to transport accumulated debris (Lustig, 1965). Others note that transitional climatic phases are critical. Weathered mantles produced in a humid phase are mobilized by rare events when the climate changes to an arid one (Hunt and Mabey, 1966). It has also been proposed that fan erosion and sedimentation go hand in hand as elements of a steady-state system. (Denny, 1965). This last hypothesis holds that there is no reason to invoke environmental change to explain alternations of process on alluvial fans. Landsat E-1400-04352-7, August 27, 1973.

Continue to Plate F-19| Chapter 4 Table of Contents.| Return to Home Page| Complete Table of Contents|