|

|

|---|---|

| Plate C-12 | Map |

|

|

|---|---|

| Plate C-12 | Map |

At 18°30' S latitude, just south of the Chile/Peru border near the Chilean frontier city of Arica, the western coast of South America makes a sharp bend from its southeasterly trend in Peru to a nearly southerly direction. North of the bend, in Peru, alluvial fans drain the desert piedmont of the Andes directly to the Pacific. Only two small mountain blocks in the northwestern corner of the image obstruct the direct connection of alluvial fans to the shore zone (A). One of them is bisected by the lower course of the Rio Sama, reflecting a late Cenozoic history similar to that of the area farther south, in Chile (Tosdal et al., 1984).

The image covers the heart of the Atacama Desert, said to be the driest on Earth (2 mm in 30 years at Iquique). In many places, no measurable rain has ever fallen. Because of the cold ocean current offshore, coastal fogs provide moisture for a few highly specialized shrubs, but most of the ground is completely bare. Rain or snow falls in limited amounts in the mountains, however, and in the inland valleys (C), irrigated agriculture is possible.

| Figure C-12.1 | Figure C-12.2 |

|---|---|

|

|

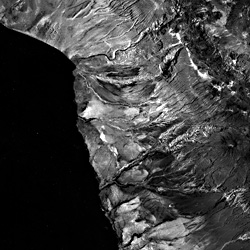

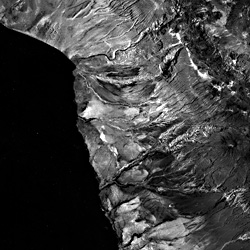

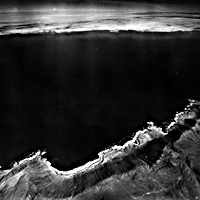

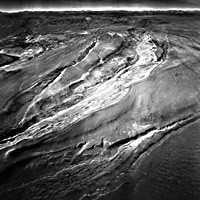

The sharp change in direction of the coast in Chile is controlled by the Cordillera de Costa (Coastal Range) that rises about 1000 m above sea level (B). On its seaward side, the Coastal Range has been eroded into a spectacular scarp (Figure C-12.1), in many places fully as high as the flattened summits of the Range. This scarp runs from Arica (18.5°S) to Taltal (25.5¯ S), a distance of more than 800 km. Its average height is about 700 m; in places, the relief from sea level may reach 2000 m. The cliff base commonly is almost at the coastline; typically, a narrow emergent abrasion platform has been cut into the scarp by waves (mainly during storms and tsunamis). The Coastal Range itself was beveled by early in the Cenozoic Era and has been uplifted only since the Miocene Epoch. The uplift created a barrier to the westward drainage of the Andes, which were experiencing tectonic uplift and massive explosive volcanism at the same time. For example, the large volcano in the lower right part of the scene is 4900 m high. The eroded sand, gravel, and volcanic ejecta (Figure C-12.2) from the Andes were trapped against the Coastal Range and filled the longitudinal tectonic valley on the western flank of the Andes to a depth of 900 to 1000 m (Ericksen, 1981; Galli, 1967; Mortimer and Saric 1972, 1975). In relatively recent geologic time, perhaps in the Pliocene or Pleistocene Epoch, the alluvial filling over topped the Coastal Range in a few places. Having spilled over the mountains into the sea, the rivers cut deep gorges across the mountains and eroded headward across the longitudinal valley to the base of the Andes. The spectacular gorges or quebradas (Figure C-12.3) are over 800 m in depth near the coast, but the steep gradients of the gorge floors rise inland rapidly and the entrenchment across the interior plains is no more than a few hundred meters. The cutting of the gorges across the Coastal Range may have been aided by coastal retreat under powerful wave attack.

The continental shelf off Northern Chile's coast is less than 10 km wide and maybe the result of wave erosion across tectonic blocks similar to the exposed coastal ranges. An alternative hypothesis is that the present coast is controlled by north- south trending faults that have dropped the seaward side of the Coast Range below sea level. Brüggen (1950) considered the scarp to be primarily tectonic in origin. Mortimer and Saric (1972) contend that tectonic movement has only uplifted a scarp caused by continued marine erosion against a subsiding coastline. Paskoff (1980) treats the present cliffs as a modified fault scarp retreating inland by bench-cutting wave erosion from Miocene onward and influenced also by glacio-eustatic movements in the Quaternary.

| Figure C-12.3 |

|---|

|

Southward from the extreme southern edge of the view, the coast is reported to have flights of uplifted marine terraces cut into the cliffs. Apparently, erosion of the coastal cliffs has been so rapid in the northern section that all trace of terraces has been removed (Mortimer and Saric, 1972, p. 162).

The continental shelf is negligibly narrow along this part of the South American Coast. Alluvium carried to the coast by infrequent flash floods is either trapped in submarine canyons and transported into the deep Peru/Chile submarine trench, or is swept northward by powerful currents. The only large beach would be in the 30-km coastal segment in Peru from the Chilean border north to Rio Sama. Landsat 1155-14102-6, December 25, 1972.

Continue to Plate C-13| Chapter 6 Table of Contents.| Return to Home Page| Complete Table of Contents|