|

|

|---|---|

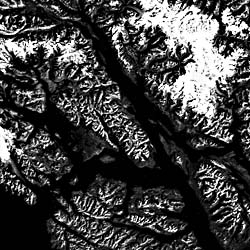

| Plate C-5 | Map |

|

|

|---|---|

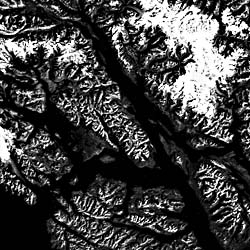

| Plate C-5 | Map |

Glacier Bay National Monument, northwest of Juneau, Alaska, is a vast area of mountain ice fields, glaciers, and fjords. It covers about 14 000 km2, including most of the eastern half of the scene north of Icy Strait. Since their European discovery in 1794, some of the tidewater glacier termini have shrunk more than 100 km. Glacier Bay was completely filled with ice to its junction with Icy Strait in 1794. By the time the area was visited by the noted naturalist, John Muir, in 1879, the ice front had retreated 77 km and had divided into numerous tidewater tributary glaciers. By the first decade of this century, there were 11 tidewater glaciers, but some that had been popular tourist attractions were no longer accessible (Tarr and Martin, 1914). Now there are about 16 separate tidewater ice fronts, as continued shrinkage of the ice dismembers the former great ice streams. From time to time, one or more of the glaciers has surged forward for a few years, then resumed its general retreat.

The fjords of Glacier Bay (Figure C-5.1) are strongly controlled by tectonic and structural lineaments. The Chatham Strait fault nearly bisects the image from top to bottom slightly oblique to the 135th west meridian. Right- lateral strike-slip faulting totaling 200 km has been suggested for this fault (Lathram, 1964). The Chugach/St. Elias fault has formed a zone of crushed and weakened rocks parallel to the coast across the southwest corner of the scene.

| Figure C-5.1 | Figure C-5.2 |

|---|---|

|

|

South of the scene, the two faults merge into the Fairweather fault, a major tectonic boundary between terranes that have no obvious genetic relation to each other, and may have been translocated thousands of kilometers northward to be accreted onto the western edge of North America by lithospheric plate motions (see Plate T-9).

Erosion by rivers and glaciers has carved deep trough- like valleys along the tectonic lineaments. Some valleys extend radially from the centers of the large Glacier Bay and Taku Ice Fields. Fjords are glacier troughs, eroded below sea level and now submerged. An excellent example is Tracy Arm (Figure C-5.2) off the lower right edge of the Plate.

Tides in Glacier Bay range up to 7 m in amplitude. The combination of deep fjords, powerful tidal currents, and very recent deglaciation has produced a coastal landscape devoid of any depositional landforms except for outwash deltas at the fronts of some retreating glaciers. There are almost no beaches except for gravel pockets in coves. Icebergs breaking from the receding glaciers are a sight witnessed by thousands of tourists each year, mostly from the safety of a ship well offshore passing along an inland passage (Figure C-5.3) such as Chatham Strait.

| Figure C-5.3 | Figure C-5.4 |

|---|---|

|

|

It is typical of tectonic coasts to have strong structural lineations, in this region accentuated by glacial erosion. When such lineations are parallel to the coast, Suess (1888) designated the coast as a Pacific type, as in this scene and in Plates C-9 and C-10. We now interpret Suess's Pacific-type coasts as typical of converging plate margins, where active tectonic compression is deforming the edge of the continental crust.

Because of either rapid postglacial isostatic uplift or active tectonism, the region of Glacier Bay is experiencing exceptionally rapid emergence in recent decades. Sites of tide gages that were installed in the late 1930s had risen more than 60 cm when the sites were reoccupied in the 1960s (Clark, 1977; Hicks and Shofnos, 1965). Maximum uplift rates near the center of the National Monument approached 4 cm per year. Studies are in progress to determine if the uplift is an isostatic response to the recent rapid reduction in the mass of glacier ice or if it is possibly precursory movement prior to a major earthquake in the region.

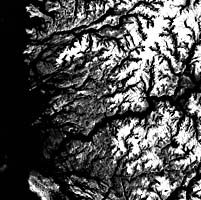

Figure C-5.4 is a Landsat view of western Norway, from whence the name "fjord" has been given to drowned coastal glacial valleys. Here the fjords are narrower, but some extend inland for more than 150 km. Because the structural grain of the Norwegian terrain is oblique or perpendicular to the coast, many fjords extend far inland rather than paralleling the outer coast as they do on the Pacific-type coast of Alaska. Landsat 1175-19330-7, September 6, 1974.

Continue to Plate C-6| Chapter 6 Table of Contents.| Return to Home Page| Complete Table of Contents|